Home • Cacao • Specialty Cacao • Bean-to-Bar Making Process

BEAN-TO-BAR

MAKING PROCESS

BEAN-TO-BAR

MAKING PROCESS

CONTENTS

The following article takes you inside the world of Mathieu Robin, in charge of transforming cacao beans into exceptional bars for the eponymous house, created by his father in 2013 in Périgueux, France.

Through a chronological journey of the bean-to-bar production process, we explore the philosophy and method behind bean-to-bar chocolate making, and how a maker’s unique approach influences the final product.

This is more than a report; it’s an in-depth dive into Mathieu’s passion for cacao. Our gratitude goes to Mathieu for sharing his expertise with us and to Hervé Robin’s team for their warm welcome and dedication to the art of chocolate-making.

INTRODUCTION

“Bean to bar” is both a designation and an added level of precision required to truly understand proper chocolate craftsmanship. But why?

Streets around the world are lined with storefronts bearing the names of chocolatiers—makers, artisans, or confectioners. Yet these titles rarely hint at an unspoken truth: most of these makers don’t work with cacao beans at all.

As Carla Martin (executive director of the Institute for Cacao and Chocolate Research) puts it: sizing the craft chocolate market is “a challenge due to the niche character of craft chocolate and specialty cacao.”¹

Estimates from specialized sources such as the International Institute of Chocolate and Cacao tasting² (IICCT) suggest that roughly 95% of chocolate makers and manufacturers worldwide use pre-made industrial chocolate, supplied by a handful of large-scale manufacturers, as the primary ingredient in their confections.

The remaining 5% are craft chocolate makers who choose a different approach—similar to winemakers who care about terroir, grape varieties, and artisanal processes. They work directly with cacao beans, creating chocolate from scratch. This commitment demands meticulous effort, patience, and a willingness to embrace unpredictability. Like fine wine, each batch of bean-to-bar chocolate reveals its own unique flavors.

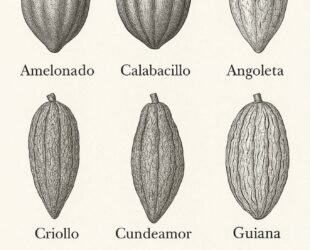

1. SOURCING

The journey begins long before production and highlights the distinctiveness of craft chocolate. Sourcing, involves finding fine or specialty cacao beans from farms, plantations, or cooperatives. This is where producers grow cacao trees, harvest pods, and carry out essential post-harvest processes, such as fermentation and drying. These steps are crucial for preserving beans and ensuring the final chocolate’s quality.

Sourcing can be done either in person or through specialized intermediaries. In the first approach, makers travel to cacao-producing countries to meet farmers and understand their practices. Alternatively, makers work with sourcers who provide beans aligned with their desired profiles, such as specific aromas, genetics, or terroirs.

Mathieu prefers the latter, collaborating closely with sourcers to create test batches—small-scale chocolate productions—to evaluate a cacao’s potential. Once satisfied, he places an order, and the sourcers handle importing the beans to his workshop.

2. HAND SORTING THE BEANS

Exceptional chocolate demands not only high-quality beans and agricultural practices but also meticulous craftsmanship. To be specific, the bean-to-bar process requires precision and a commitment to excellence.

A rigorous method in essence but Mathieu isn’t satisfied with it alone. Devoted to his creations, he moves the cursor from rigor to exigency and shares with us his infinite quest for perfection. Not without recalling ikigai and the philosophy linked to Japanese craftsmanship, he tells us how carefully executing and repeating each gesture every day renews a virtuous cycle for him. Deepening his mastery, appreciating the results: a pace in the making that creates a calming balance between control and detachment.

Once the bags are opened, each batch begins with hand-sorting the beans to remove defects such as unripe or over-fermented pieces, or debris.

3. ROASTING

After sorting, beans are roasted—slowly heated and dried without being burned—to develop their aromas and flavors. Mathieu uses an oven with perforated plates, ensuring even heat distribution and uniform roasting without stirring.

Depending on the desired aromatic profile, each bean-to-bar maker defines its own roasting parameters (durations and temperatures), which differ for each batch, even those coming from the same plantation. Indeed, variations in growing conditions (mostly weather) and post-harvest processing impact the beans’ quality. Adaptation is therefore essential.

Again, exigency here is key for Mathieu.

Rather than relying on common versatile profiles that have nothing left to prove, he carries out numerous tests ahead of production in order to achieve a result that honors the specificities of the actual bean.

Those are precious data, proper manufacturing secrets since they make the craft chocolate maker’s “touch” and are sometimes enough, for the most seasoned pallets, to recognize the author of a bar.

Beyond flavor, roasting enhances cacao’s digestibility, optimizes nutritional qualities, and eliminates residual bacteria.

Unlike industrial practices, which rely on high-temperature, quick roasting that burns beans and necessitates flavor masking, the bean-to-bar approach emphasizes gentle, slow roasting to preserve nutrients and natural flavors. If you ever found regular dark chocolate to be “too bitter”, blame it on the roasting.

4. CRUSHING & WINNOWING

Once roasted, beans are cooled and then crushed in a winnower to produce cacao nibs. A two-in-one step: winnowing separates the nibs from the husks, using airflow to ensure a clean separation. Mathieu runs the beans through the winnower three times to achieve finer nibs with minimal husk residues.

5. SORTING THE NIBS

Before grinding, nibs undergo another meticulous hand-sorting process to remove any remaining husk fragments. This step, though time-consuming, is essential for achieving a smooth texture and pure flavor by reducing the presence of fibers to its bare minimum.

Mathieu invests as much time in this stage as in all other steps combined, underscoring his commitment to excellence.

6. LOADING THE MILL

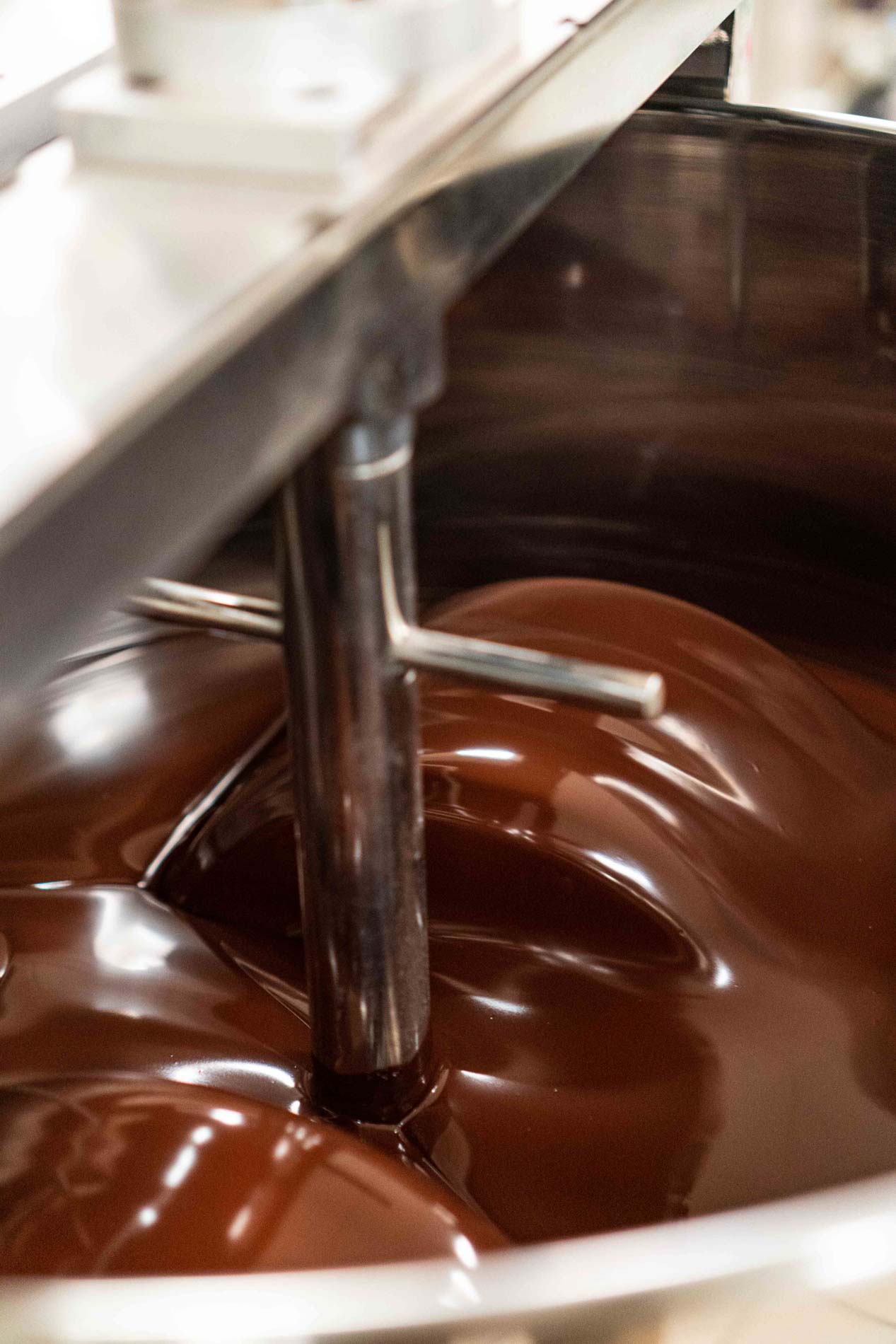

The transformation into chocolate begins with grinding the nibs into a paste. Mathieu uses a stone grinder, a hybrid machine blending artisanal and semi-industrial techniques. It allows to process a significant quantity of cacao, while limiting the transformation’s intensity.

In addition, it also plays the role of a conch, a machine present in most chocolate factories. Its role is to stir the paste for 24 to 72 hours, mainly to homogenize the texture while eliminating certain undesirable aromatic compounds.

Beans contain around 50% of fat (cacao butter) in their constitution. It is released under the pressure and friction exerted by the wheels. Loading is done gradually, adding nibs kilogram by kilogram in order to ease the mill’s motion. A couple of hours are enough for the mill to transform this rough mass into a viscous paste, indicating to Mathieu that it’s time to add the second and final ingredient of his recipe: sugar.

This is one of the key principles of the bean-to-bar method: less is more.

Two-ingredient chocolate first appeared in the late 2000s in the U.S. Since then, conscious makers’ list of ingredients started to shrink. The addition of flavorings, lecithin or cocoa powder is prohibited.

Some bean-to-bar makers retain the addition of cacao butter in their recipe. Mathieu prefers to use what the beans have to offer and adapts his process accordingly. The mill’s mixing time therefore varies depending on the batch, which allows him to achieve the desired homogeneity.

Te grinding step is often synonymous with demarcation in the bean-to-bar world since it enables the search for a signature texture: silky, rough, or somewhere in between. Mathieu chose his side, that of finesse.

7. UNLOADING THE MILL

After 72 hours of operation, sugar and cacao coexist homogeneously and the chocolate’s aromatic profile displays complex flavors and subtle notes.

A grindometer test is performed to ensure particles are reduced to 15 microns, creating a velvety mouthfeel. If the test is conclusive, it is time to unload. Final precautions before the brown gold flows: preheating the strainer (serving as a last filter) and the container in order to avoid thermal shock and premature crystallization of the cacao butter.

From this moment on, the chocolate will no longer undergo any processing. However, it has not yet completed its transformation process. Packaged in 3kg blocks, it is sealed and stored for several months and begins a maturation process. The chocolate will “work”, its aromas will evolve, sometimes going as far as to deceive the artisan in his projections when releasing a block for moulding.

Here, the magic of chocolate is in full swing: despite the extreme finesse with which cacao is processed, it’s up to the bean to have the last word on the flavors it’ll reveal.

A lesson in humility that Mathieu welcomes with open arms at each execution. He shares with me the pleasure he sometimes feels in being surprised, rediscovering the profiles of certain cacaos, refining his understanding of his decisions’ impact. Working with cacao beans is an endless learning experience for him.

The cacao processed here on the pictures is a Chuao, a well-known designation amongst fine chocolate enthusiasts. It comes from an eponymous plantation located in Venezuela. More than a variety, this name designates what would be an equivalent of a cépage, since it takes into account genetic and geographical characteristics.

Once again like wine, the qualities of a cacao are evolving and determined harvest after harvest, taking into account a large number of factors. A country of origin, or a so-called variety does not provide enough information to judge the quality of a chocolate, just as a “vin de France” or a Chardonnay indicates nothing about a wine’s quality.

Cultivation practices, climate, orientation of a plot, altitude, rainfall… Dozens of uncontrollable parameters subtly alter the flavors of each harvest. A renewed challenge for the craft chocolate maker, and a unique taste experience, specific to each bar, for those lucky enough to taste it.

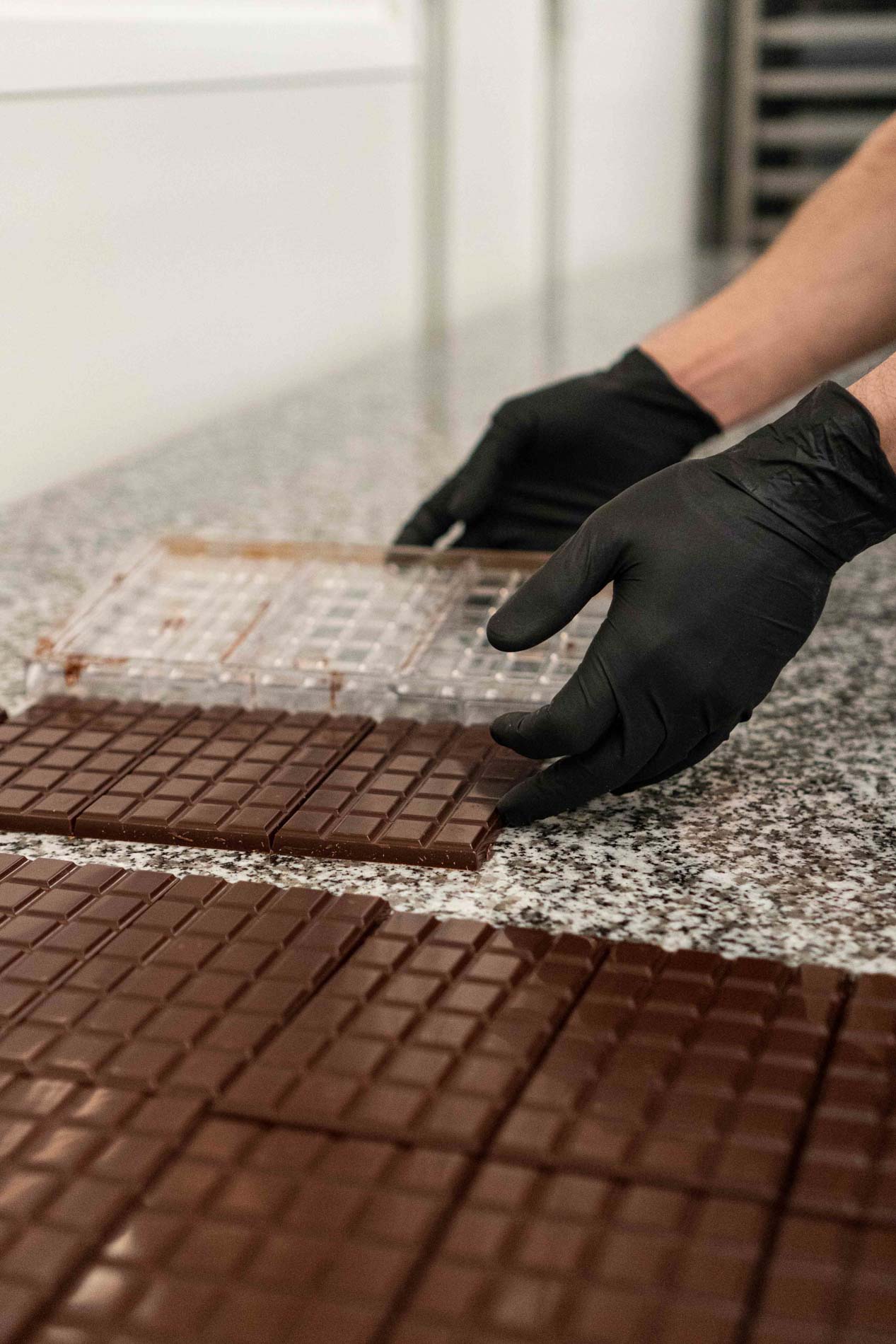

8. TEMPERING & MOLDING

Months later, the chocolate undergoes its final transformation. Tempering involves carefully melting and cooling the chocolate—following a specific temperature curve—to achieve optimal crystallization of cacao butter, resulting in a glossy finish, creamy texture, and satisfying “snap.” Using a tempering machine, Mathieu fills molds with precision, creating up to 450 bars daily.

After cooling, the bars are unmolded, brushed, and polished to perfection, marking the culmination of cacao’s journey from bean to bar.

This step completes cacao’s transformation into chocolate. A long journey between Venezuelan soils and the Périgourdin workshop, between raw beans and grand cru chocolate. A three-day cycle that Mathieu repeats throughout the seasons, in search of finesse, novelty, mastery, subtlety.

CONCLUSION

Much more than a treat or guilty pleasure, bean-to-bar chocolate celebrates cacao in its purest form, encapsulating the synergy between nature’s work and that of a few human beings. Each bar invites you to slow down and savor its complexity as it melts on your tongue. This is not chocolate to be chewed—it is an experience that reveals its depth with patience.

Take the time to appreciate these bars, and you’ll uncover flavors as unique and intricate as the journey that brought them to life.

SOURCES

REFERENCES

- Martin, Carla, “Sizing the craft chocolate market,” Fine Cacao and Chocolate Institute (blog), August 31, 2017, https://chocolateinstitute.org/blog/sizing-the-craft-chocolate-market/.

- International Institute of Chocolate and Cacao Tasting. IICCT. https://www.chocolatetastinginstitute.org.