HISTORY

& CHRONOLOGY

HISTORY

& CHRONOLOGY

CONTENTS

- The Origins of Cacao

- Evidence of First Use (3300 BCE)

- Pre-Colonial Period (3300 BCE – 1500 BCE)

- Spanish Contact Period (16th c.)

- Cacao Spreads in Europe (16th c. – 19th c.)

THE ORIGINS OF CACAO

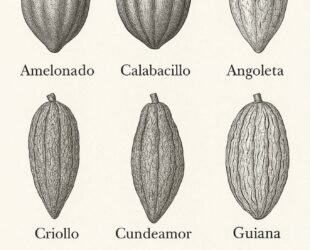

Theobroma cacao, the tree from which cacao is grown, originally developed in the upper Amazon basin in South America. This area, which includes parts of modern-day Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador, was the birthplace of cacao ten million years ago1, and more recently, the cradle of its early domestication and diversification.

Archaeological findings reveal that cacao was cultivated and used in South America as far back as 5,300 years ago, with evidence pointing to early domestication in the southern Amazon region of Ecuador.2 Over time, cacao spread beyond its Amazonian origins through human trade and migration, eventually reaching Central America. There, it became culturally and economically significant among peoples like the Pipil, the Olmecs, the Mayas, the Mexicas (Aztecs) and many more.

Image by

Evidence of First Use (3300 BCE)

The first unequivocal evidence of cacao use dates back approximately 5,300 years ago, attributed to the Mayo-Chinchipe culture in what is now southeastern Ecuador. This discovery, made at the archaeological site of Santa Ana-La Florida, represents the earliest known use of Theobroma cacao.

Researchers identified three lines of evidence: starch grains characteristic of domesticated cacao, traces of theobromine (a chemical unique to cacao seeds), and DNA fragments bearing gene variants of domesticated cacao (see Motamayor’s paper, cited below).2 The artifacts were found in household contexts and elite tombs, hinting at its cultural significance.

These findings suggest that cacao was used in various forms—possibly as food, drink, medicine, or for ceremonial purposes. Such evidence underscores the Amazon basin’s role as the cradle of domesticated cacao and highlights how archaeological residues can illuminate ancient practices.

This groundbreaking discovery reshaped our understanding of cacao’s history, as it predates the previously assumed earliest uses by Mesoamerican cultures by about 1,500 years (see Powis’s paper cited below).3

Chemical residue analysis provided undeniable proof: traces of theobromine and caffeine—unique markers of cacao when combined—have been found in ceramic vessels from the ancient Mokaya and Olmec cultures of present-day Mexico and Central America.

These discoveries, made through chromatography and mass spectrometry, confirmed that cacao was not only consumed but likely fermented into a beverage, possibly for ritual or elite purposes. Archaeological findings, including decorated pottery with depictions of cacao pods, further reinforce its deep cultural significance.

For a detailed look on ancient cacao uses and roles, check out our dedicated article: Uses and Roles of Cacao in Ancient Mesoamerica.

Pre-Colonial Period (3300 BCE - 1500 CE)

In the time period between these early-use discoveries and the records of Spanish conquistadors, numerous evidences of cacao use reveal its widespread cultural, economic, and ritual significance across diverse societies in the Americas. Beyond the well-documented Maya and Aztec traditions, cacao use extended to other regions and cultures, highlighting its importance throughout pre-Columbian history.

In the highlands of Central Mexico, cacao was already known and consumed by societies like those at Teotihuacan (100 BCE–550 CE), where cacao residues have been found in pottery, indicating its role in elite feasting and ritual contexts.4 By the Late Classic period (600–900 CE), cacao had become a widely traded commodity, moving between regions where it could not be grown—such as highland zones—and tropical lowlands like Soconusco (modern Chiapas), which became a major production center.5 Cacao also reached North American Southwest, as evidenced by residues found in ceramics at sites like Chaco Canyon (circa 900–1150 CE).6

These findings suggest long-distance trade networks connecting Mesoamerica to regions as far north as present-day New Mexico, where cacao was likely used in ceremonial contexts. Further south, in Central America, early societies such as the Nahua-speaking Pipil and others in Honduras and Nicaragua incorporated cacao into their rituals and economies. Archaeological evidence from these regions includes vessels with theobromine traces and depictions of cacao in art.

Additionally, cacao was used by cultures along the Pacific coast of South America, such as the Valdivia culture in Ecuador (circa 1500 BCE–500 BCE)7. These evidences—ranging from chemical analyses of pottery residues to depictions of cacao in art—demonstrate that cacao was far more than a foodstuff. It was a sacred substance, a currency, and a symbol of power that connected diverse cultures across vast distances long before European contact.

Spanish Contact Period (16th Century)

The contact period with the Spanish marked a transformative era for cacao, reshaping its cultural and geographic trajectory in South and Central America. The first recorded encounter between Spanish explorers and cacao occurred in 1502 when Christopher Columbus came across a Maya trading canoe carrying cacao beans in Nicaragua. Initially, Columbus mistook the beans for almonds and dismissed them due to their bitter taste.

It wasn’t until Hernán Cortés’s expedition and meeting with the Aztec empire in 1519 that the true significance of cacao was recognized. He and his men noticed that indigenous elites consumed a bitter, frothy chocolate drink, often mixed with chili, vanilla, and other spices; they understood that cacao was regarded as a divine substance, locals using beans as both a currency and a ritual beverage.

At first, the Spaniards found the unsweetened drink unpalatable, but they soon recognized its value, especially after observing its energizing effects. As they adapted to New World (Americas) customs, they experimented by adding sugar and cinnamon, making it more appealing to European tastes.

In 1528, Cortés brought cacao beans and the necessary equipment to prepare the drink back to the Spanish court, presenting it to King Charles V. Again, with the help of sugar, the bitter drink quickly became popular among Spanish nobility. This discovery led to the establishment of cacao plantations in the New World and the beginning of a profitable trade, with Spain monopolizing the cacao market for the next hundred years, fueling its colonial expansion.

From there, the ritual, cultural and medicinal aspects of cacao started to fade gradually. The Spanish exploited existing cultivation systems, forcing Indigenous communities to supply cacao as tribute and expanding its production into the Caribbean and other regions of the world.

Cacao Spreads in Europe, Fades in its Cradle (16th-19th Century)

The early evolution of cacao in Europe marked a dramatic shift from its sacred and ritualistic roots to a symbol of luxury and global commodity, setting the stage for its eventual spread to Africa and beyond.

The 16th century saw cacao captivating the royal courts as a decadent drink for European elites. By the 17th century, chocolate spread across France, Italy, and England, becoming a fashionable indulgence in aristocratic circles and eventually reaching broader audiences with technological advances like the cocoa press in 1828.

However, the growing European appetite for chocolate came at a devastating cost. Colonial powers expanded cacao cultivation beyond the Americas to West Africa by the late 19th century, exploiting enslaved laborers under brutal conditions on plantations in places like São Tomé, Príncipe, and Ghana.

This shift not only entrenched systemic exploitation but also decimated native cacao-growing cultures in Central and South America, as Indigenous communities were displaced or forced into labor systems that eroded their traditional ways of life. The globalization of cacao production thus reflects both its rise as a beloved commodity and the dark legacy of colonialism and slavery that fueled its spread.

The Industrialization of Cacao and Chocolate Production (19th-21st century)

The industrialization of cacao and chocolate in the 19th century revolutionized its production, transforming it into an accessible treat. The pivotal moment came in 1828, when Dutch chemist Coenraad Johannes Van Houten invented the hydraulic press, a groundbreaking machine that separated cocoa butter from cacao solids. This innovation enabled the creation of powdered cocoa, making chocolate smoother, easier to mix, and more affordable for mass production.

Building on this, British chocolatier Joseph Fry introduced the world’s first solid chocolate bar in 1847 by recombining cocoa butter with sugar and cocoa powder into a moldable paste. The Swiss soon advanced these developments: in 1875, Daniel Peter invented milk chocolate by combining chocolate with Henri Nestlé’s powdered milk, creating the creamy texture beloved today.

Just a few years later, in 1879, Rodolphe Lindt developed the conching process, which refined chocolate’s texture and flavor by heating and agitating it over time. These milestones not only democratized chocolate consumption but also laid the foundation for global production. However, this industrial boom came with consequences.

Where are we today?

Cacao is now almost only seen as a mere ingredient of chocolate, a mass-consumed product, with the global chocolate market projected to reach $172.89 billion by 2030. The industrialization of chocolate production devalued cacao as a raw material, reducing the recognition of its cultural significance and the labor-intensive work behind it.

Farmers—90% of whom are smallholders cultivating less than 5 hectares—earn a fraction of the profits from a global supply chain dominated by multinational corporations. Modern slavery remains a grim reality in cacao production, particularly in West Africa, which supplies over 70% of the world’s cacao. Forced labor, including child labor, persists due to systemic poverty, volatile market prices, and exploitative practices that prioritize profit over human rights.

Meanwhile, industrial processing methods have further distanced consumers from cacao’s origins. While technological advances have improved efficiency and lowered costs, they have also led to quality compromises and environmental degradation through unsustainable farming practices.

Global chocolate consumption is highly uneven: while Europe leads with per capita consumption as high as 11.8 kilograms annually in countries like Switzerland, regions such as Asia consume far less. This disparity underscores how cacao’s colonial history has concentrated wealth and benefits in industrialized nations while leaving producer regions impoverished.

Climate change now compounds these issues, making traditional cacao-growing regions less viable due to rising temperatures and unpredictable weather patterns.

Today’s chocolate industry reflects both the enduring appeal of cacao and the systemic inequalities rooted in its colonial past. Efforts toward ethical sourcing and sustainability are growing but remain insufficient to address the exploitation embedded in the global cacao supply chain. Without systemic change, the industry risks perpetuating the very injustices that have defined its history.

WHERE DO WE WANT TO GO?

From its wild Amazonian roots to becoming a revered crop across South and Central America, to then being displaced around the world to meet an ever-rising demand, cacao has had a fascinating journey. It left a lasting imprint in its cradle that can still be felt and witnessed today, for those who look close enough.

Some of its traditions have persisted, preserving a sense of purpose in its use and consumption. Now, as cacao metaphorically “comes out of the jungle”—to borrow a Mayan myth—it is shedding new light on what has, for the past two centuries, been wrongly reduced to a mere commodity.

In the late 2000s, a wave of Westerners, particularly in Guatemala, rediscovered cacao’s essence and began sharing it in meaningful ways. Over the last two decades, this growing awareness has given rise to a niche movement centered around what is now known as ceremonial cacao.

Alongside it emerged the modern concept of “cacao ceremonies”—gatherings where participants consume pure cacao drinks, often incorporating rituals or spiritual practices. As the idea spread, it evolved organically, finding its place at the intersection of modern spirituality, holistic well-being, and esoteric exploration. However, this fusion has also led to a complex web of interpretations, blending contemporary Western perspectives with ancient traditions.

Despite the historical complexities and the cultural shifts cacao has undergone since the 16th century, there is a need to clarify its narrative. By deepening awareness and understanding of cacao’s many facets—historical, cultural, botanical, medicinal, aromatic, and spiritual—we can ensure that it is appreciated in a more authentic and informed way. Now is the time to reframe its story, offering everyone access to the aspects that resonate most with them, and most importantly, paying respect to its origins.

To achieve this, we believe it is essential to:

- Establish proper designations for authentic cacao paste and drinks that accurately reflects its quality and cultural significance.

- Bridge the gap between Origin Cacao and other key sectors of the industry, such as bean-to-bar chocolate, which emphasizes ethical sourcing, direct trade with farmers, sustainable agricultural practices, and quality at every stage of production.

- Educate both consumers and professionals on the rich diversity of cacao.

- Elevate and amplify the voices of those at the heart of cacao’s origins.

This is what drives us at Cacao Insights.

SOURCES

REFERENCES

- Richardson, James E., Barbara A. Whitlock, Alan W. Meerow, and Santiago Madriñán. 2015. “The Age of Chocolate: A Diversification History of Theobroma and Malvaceae.” Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 3: 120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2015.00120.

- Motamayor, Juan Carlos, et al. 2008. “Geographic and Genetic Population Differentiation of the Amazonian Chocolate Tree (Theobroma cacao L.).” PLoS ONE 3 (10): e3311. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003311.

- Powis, Terry G., et al. 2007. “Cacao Use and the San Lorenzo Olmec.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104 (48): 18937–40. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0708815104.

- Des Lauriers, Matthew A. 2010. “Gods, Cacao, and Obsidian: Early Classic (250–650 CE) Interactions between Teotihuacan and the Southeastern Pacific Coast of Mesoamerica.” Latin American Antiquity 21 (3): 227–51. https://doi.org/10.7183/1045-6635.21.3.227.

- Coe, Sophie D., and Michael D. Coe. 2013. The True History of Chocolate. 3rd ed. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Crown, Patricia L., and W. Jeffrey Hurst. 2009. “Evidence of Cacao Use in the Prehispanic American Southwest.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (7): 2110–13. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0812817106.

- Lanaud, Claude, et al. 2024. “A Revisited History of Cacao Domestication in Pre-Columbian Times Revealed by Archaeogenomic Approaches.” Science Advances 10 (21): eadl4885. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adl4885.

BACKGROUND MATERIAL

• Patchett, Marcos. The Secret Life of Chocolate. London: Aeon Books, 2020. ISBN 978‑1‑911597‑06‑3.

• Cameron L. McNeil, ed., Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao, Maya Studies. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2006. ISBN 9780813033822.

• Coe, Sophie D., and Michael D. Coe. The True History of Chocolate. 3rd ed. London: Thames & Hudson, 2013. ISBN 978‑0‑500‑29068‑2.