USES & ROLES OF CACAO

IN ANCIENT MESOAMERICA

USES & ROLES OF CACAO

IN ANCIENT MESOAMERICA

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

For many Indigenous peoples of the Americas, both ancient and modern, cacao held deep cultural and spiritual significance—a role that was gradually erased through colonization and cultural suppression. Once revered as a sacred tree and fruit, cacao was reduced to a mere commodity in the last few centuries, a rapid decline compared to the span of its long history.

At Cacao Insights, our mission is to help restore a deeper appreciation for cacao by sharing its many dimensions and reigniting interest in its true legacy. However, before we can reshape the modern narrative around cacao, it is essential to understand its original, complex socioeconomic role across different cultures and time periods. While it would be impossible to fully capture the customs of every people that cherished cacao in a single article, we aim to highlight a well-documented portion of its history to illustrate why it is far more than just a food.

Among the many roles cacao played, some are particularly well-recorded, especially in Maya and Aztec history. Below, we explore some of its most commonly depicted uses in these two civilizations, offering an overview of its profound cultural significance.

BELIEFS & RITUALS

While discussing this topic, it’s important to have in mind that Mesoamerican societies tied an intimate relationship with their surrounding natural world. To cite Simon Martin, author of Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion1: “[Fauna and flora] were embedded in their spiritual outlook. The crops that fed and enriched them [like maize and cacao] were especially charged with religious sentiment and took pivotal roles in their mythic narratives.”

Cacao held immense spiritual importance, often regarded as a divine gift. Both the Maya and Aztecs incorporated cacao into their creation myths, believing it was discovered by the gods in sacred mountains and shared with humanity. The Maya associated cacao with Ek Chuah, their merchant deity, while the Aztecs linked it to Quetzalcoatl, their creator god who gifted cacao to humans before his exile. Cacao was central to religious ceremonies, where priests and nobles consumed a sacred drink made from cacao mixed with water and spices, known as xocoatl.

Cacao has a history of being tied to important life passage rituals such as births, weddings or burials. It was used in every form—from whole pods and beans to complex beverages—and was either consumed, used as adornment or gifted as an offering. It was also extensively used in rituals honoring ancestors or gods. Some of those traditions persisted to this day, despite the impacts of colonialism.

Relevant examples:

- During funerals, cacao beans and vessels were buried with the deceased to accompany them into the afterlife.

- Sacrificed captives were also granted a precious cup of the beverage right before their execution as it was believed to facilitate the transition between life and death.

These practices highlight the belief that cacao had spiritual power beyond the physical world.

Looking more closely at ancient Maya religion, cacao is depicted as a sacred tree. Cacao pods were linked to heart as both were holding a sacred fluid (analogies between blood and cacao were common). Cacao glyphs are depicted on fine vessels, ceramics, censers, façades, stelae; sculptures of stone and ceramic were devoted to it. The abundance of representations testifies for its significance.

Linked to cosmology, cacao represents the South cardinal point, associating it with shade, death and the Underworld. The North cardinal point being Maize, both crops are often depicted together as assembling polarities (for instance, the Maize god is often depicted as a personified cacao tree).

CURRENCY

For their inherent value, but also for their size and durability, cacao beans were used as a form of money, simplifying exchanges in marketplaces. To possess cacao was a sign of wealth, power and rulership across Mesoamerica. By the 7th century, the Maya and Aztecs utilized these beans for transactions (goods, work services…), tribute payments, and even as a means of debt repayment. For example, 200 cacao beans could buy a turkey or pay for a day’s labor. It is also recorded that slaves could buy their way out of forced labor in exchange for cacao beans.

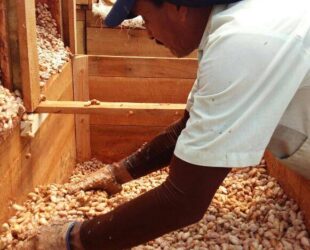

Their value varied based on quality, with plump, fully fermented ashy-colored beans commanding higher worth than inferior reddish beans. This edible currency allowed for a dual-purpose economy where beans could be consumed or traded, reflecting their deep cultural significance.

MEDICINE & VITALITY

The medicinal properties of cacao were highly regarded in Mesoamerica, serving as both a remedy and a medium for delivering other treatments. The Maya and Aztecs believed cacao could heal the body and invigorate the spirit. It was used to reduce fever, agitation, and hoarseness, as documented in the Florentine Codex, while cacao bark was applied externally to soothe burns and bronchitis.

The fruit pulp of cacao pods was thought to facilitate childbirth, and its leaves were used as antiseptics for wounds. Additionally, cacao drinks fortified soldiers in battle and were believed to enhance energy, longevity, and even sexual vitality.

The Drink of the elite: Marker of Social Status

Back in the days, cacao was a scarce and valuable resource; rulers, artists, nobles, successful merchants and warriors had the lion’s share. One of the most vivid examples of its role as a marker of social hierarchy can be seen in the tradition of feasting.

Feasting was a whole part of the Mesoamerican socioeconomic fabric. It usually consisted of banquets held by nobles for the elite to celebrate war victories, marriages, births, accession to the throne and various special occasions. During these banquets, hosts would gather substantial amounts of food to feast on, as well as high-quality craft goods—such as ceramics or cloths— and precious materials such as feathers, shells, jadeite adornments and cacao beans. These were all destined to be gifted to the guests at the conclusion of the banquet.

This gift-giving custom was an essential part of feasting. On the one hand, it allowed for reinforcing alliances and relationships as it would silently imply unspecified support for the host in the future. On the other hand, it would help fueling each guests’ own wealth and therefore perpetuating the cycle of feasting. Feasts were socioeconomic catalysts, reinforcing relationships and networks while propagating a circular movement of goods— the host would give generously and, in turn, receive when attending others’ feasts.

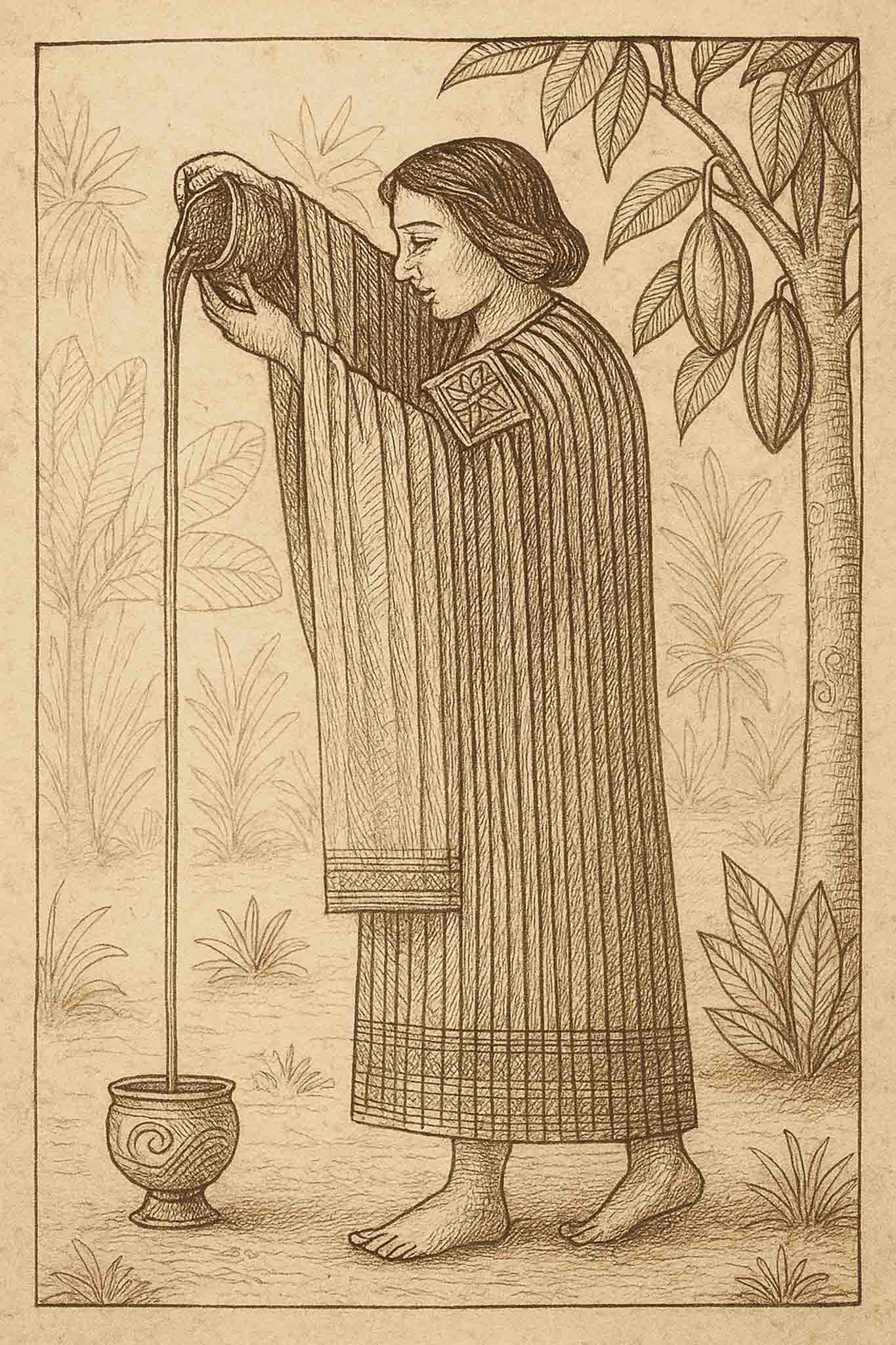

Cacao held a singular place during these celebrations. Cacao drinks were the favored beverages at these banquets and abundantly served in valuable painted ceramics (also destined to be gifted). Such access to the prized drink represented the host’s power and wealth. Their preparation would sometimes be presented as a performance during these events, formalizing hosting and the importance of gaining access to such a precious food.

CONCLUSION

The story of cacao in ancient Mesoamerica is one of reverence, complexity, and cultural depth. It was not merely consumed but celebrated as a divine gift that connected humanity with the spiritual realm while serving practical roles in trade, medicine, and social hierarchy. Today, as we enjoy cacao in its modern forms, it is crucial to remember its origins—a sacred plant that shaped civilizations.

By understanding its historical significance, we can begin to honor its legacy and reclaim its place as more than just a commodity but a symbol of cultural richness.

For a deeper dive into cacao’s history and its evolution from ancient Mesoamerica to the modern world, check out our full article on the History and Chronology of Cacao.

SOURCES

REFERENCES

- Cameron L. McNeil, ed., Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao, Maya Studies. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2006. ISBN 9780813033822.

– Chapter 8, written by Simon Martin: Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion.

BACKGROUND MATERIAL

• Cameron L. McNeil, ed., Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao, Maya Studies. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2006. ISBN 9780813033822.

– Chapter 7, written by John S. Henderson & Rosemary A. Joyce: The Development of Cacao beverages in Formative Mesoamerica.

– Chapter 8, written by Simon Martin: Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion.

– Chapter 10, written by Dorie Reents-Budet: The social context of Kakaw drinking among the Ancient Maya

– Chapter 11, written by Cameron L. McNeil, William J. Hurst & Robert J. Sharer: The Use and Representation of Cacao During the Classic Period at Copan, Honduras.

• Patchett, Marcos. The Secret Life of Chocolate. London: Aeon Books, 2020. ISBN 978‑1‑911597‑06‑3.

• Coe, Sophie D., and Michael D. Coe. The True History of Chocolate. 3rd ed. London: Thames & Hudson, 2013. ISBN 978‑0‑500‑29068‑2.