VARIETIES &

GENETIC DIVERSITY

VARIETIES &

GENETIC DIVERSITY

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

CACAO VARIETIES IS A COMPLEX TOPIC.

While the traditional categorization of cacao into Criollo, Forastero, and Trinitario is still pervasive, research has revealed that cacao diversity is far more nuanced.

This article is designed in the intent to give a broad overview of classification, clarify how to refer to different types of cacao, and describe what this diversity means.

Basics of plants classification

Before diving into what makes cacao’s rich diversity, it’s good to have a basic understanding of taxonomy: how organisms (plants, animals, fungi, microorganisms) are classified.

Zooming out, plants are usually classified as species,

→ which belong to a genus (main category),

→ which belong to a family.

The cacao tree—or Theobroma Cacao L.—is one of the twenty species that belong to the Theobroma genus, itself belonging to the Malvaceae family.

Now let’s get a tad more specific.

WHAT IS A VARIETY?

“In the ranking of the plant kingdom, plants are most often known for their species. This rank is important because it characterises a group of plants that can reproduce only between themselves. Variety is a taxonomic rank below that of species. In agriculture, a variety corresponds to a population of plants of a given species that has been selected and cultivated, often for millennia, in order to produce characteristics which meet man’s needs.”

— GEVES 1

What’s wrong with “cacao varieties”?

Or why this classification method doesn’t suit cacao?

It is now known that cacao originates from the Amazon basin and was distributed by humans throughout Central America. The first traces of its use date back to approximately 5300 years ago.2

Many Mesoamerican and Southern American civilizations are known to have use cacao. Yet they developed a practice of domestication different from the usual “plants dependent on people” form of agriculture, common in Western societies.

“The domestication of trees in tropical forests focused not only on the species but on the domestication of the forest itself.” 3 This technique would today be referred to as agroforestry. It helped transform large patches of forests into “wild” forest gardens for human purposes.

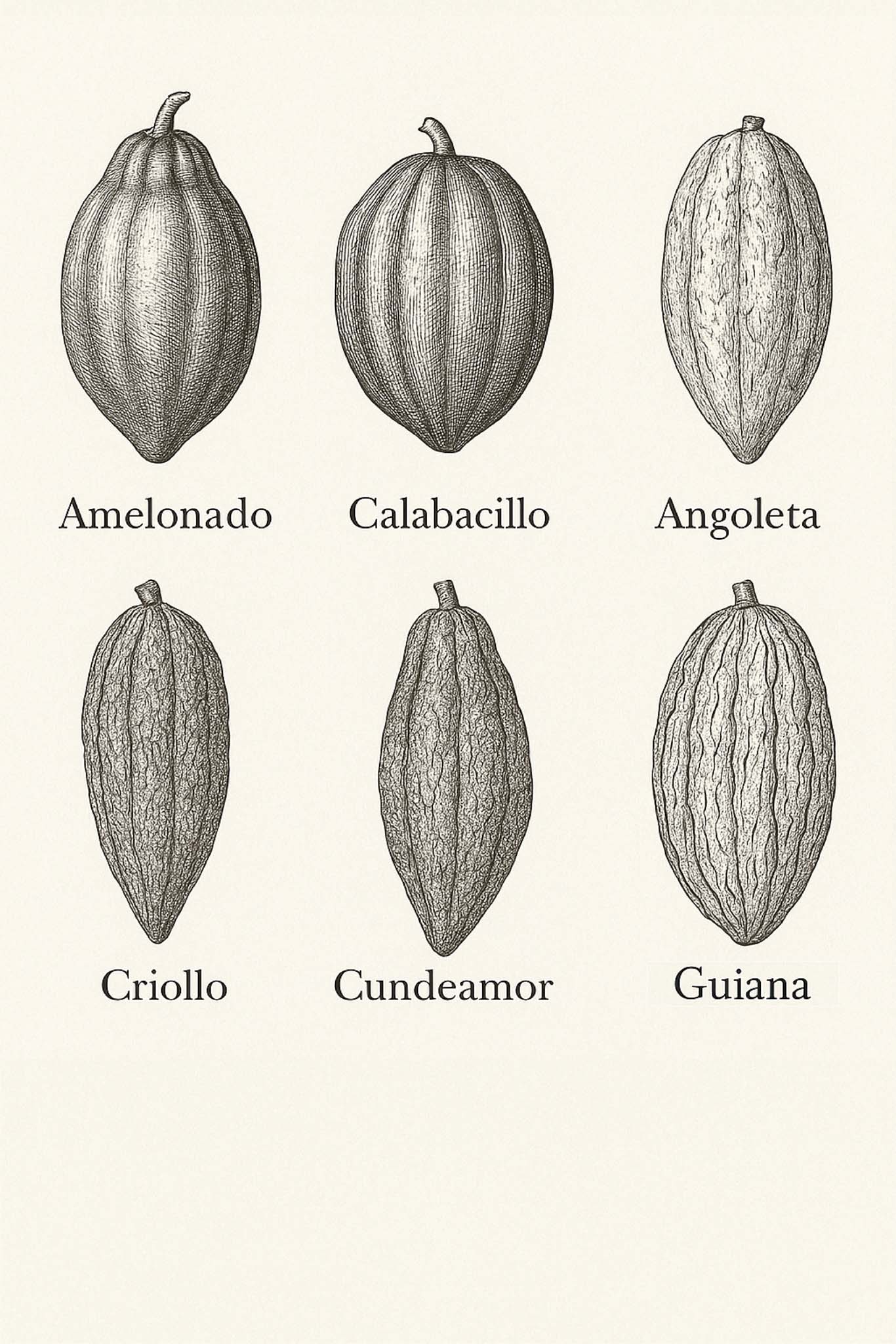

These two factors, broad distribution and enriched domestication, combined to the intricate breeding mechanisms of T. cacao caused its singular evolution and diversification. This makes it hard to differentiate so-called varieties among the cacao specie—looking at usual criteria such as fruit morphology, color, seed shape etc…— simply because no rule could differentiate its variations well enough.

Properly naming cacao’s diversity

Rather than variety, it is more relevant to talk about “genetic clusters”.

The three-legged classification—composed of Criollo, Forastero and Trinitario— was revised in 20082 after its use was definitely considered an oversimplification.

Instead, at least eleven genetic clusters have been determined, which include Amelonado, Caquetá, Contamana, Criollo, Curaray, Guiana, Iquitos, Marañon, Nacional, Nanay, and Purús.

These groups were identified through extensive genetic studies—primarily led by Juan Carlos Motamayor and his colleagues—including molecular markers and microsatellite analyses, and reflect the complex evolutionary history of cacao. This new organization is now widely known as the Motamayor classification.

Each of these clusters represents a unique genetic heritage shaped by geographical isolation, environmental adaptation, and, significantly, human intervention.

Experiencing cacao’s diversity

You might wonder: how is this diversity expressed in the cacao we have access to?

Cacao’s history has led to the development of local genetic clusters adapted to specific ecological niches. Fine distinctions within them affect flavor and composition, but also productivity, and adaptability.

For instance, the cacao Nacional from Ecuador—renowned for its floral notes and overall complex aromatic profile—is prone to disease and bears each year a rather small amount of fruits.

On a more personal standpoint, we noticed through the making of our Cacao Profiles that Chuncho beans—cacao originating from the region of Cusco, Peru—hold a noticeably higher fat content than any other cacao we experimented with so far.

Furthermore, sketching out these profiles led us to the conclusion that each cacao is responsible for its own psychoactive effect, implying that a bean’s composition might defer according to its genetics.

Understanding the genetic background of cacao allows on the one hand for more targeted breeding, helping to enhance desired traits such as disease resistance and flavor. On the other hand, it helps develop better preservation practices.

→ Another element playing a significant role in fine-tuning cacao’s diversity is terroir: how parameters like climate, soil composition, altitude or surrounding plants influence the expression of cacao. A topic we’ll discuss in another dedicated article.

SOURCES

REFERENCES

The French Variety and Seed Study and Control Group, GEVES : What is a variety?

- Motamayor, J. C. et al. Geographic and Genetic Population Differentiation of the Amazonian Chocolate Tree (Theobroma Cacao L). PloS One

BACKGROUND MATERIAL

• Cameron L. McNeil, ed., Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao, Maya Studies. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2006. ISBN 9780813033822.

— Chapter 2, written by Bletter, N. and Daly, D.C.: Cacao and its relatives in South America: an overview of taxonomy ecology, biogeography, chemistry and ethnobotany.

• Presilla, Maricel E. (2009). The New Taste of Chocolate, Revised: A Cultural and Natural History of Cacao with Recipes. Ten Speed Press.

• Lanaud, C. et al. A revisited history of cacao domestication in pre-Columbian times revealed by archaeogenomic approaches.

• Nousias, O. et al. Three de novo assembled wild cacao genomes from the Upper Amazon.